Japan’s religious landscape differs markedly from that of many other nations around the world. According to an NHK survey, only 36% of Japanese people identify as adherents to any formal religion, with 31% identifying as Buddhist and 3% as followers of Shinto. However, these statistics belie the complex relationship between the Japanese people and their religious traditions.

For most Japanese, religion exists not as a rigid set of doctrines or practices but as an integral element of cultural life. It is not uncommon for individuals to visit Shinto shrines on New Year’s Day, participate in Buddhist funeral rites, and even hold Christian-style weddings—a religious flexibility that would be unusual in many other societies. Unlike the deep religious immersion often observed in Western or Middle Eastern cultures, Japanese religious practice tends to be more situational, with religious customs incorporated into life’s milestones and seasonal observances.

A defining characteristic of both Shinto and Buddhism in Japan is their lack of compulsory practices or severe restrictions. This inherent “looseness” is likely a significant factor in how these religions have persisted in Japan’s increasingly individualistic modern society.

Shinto and Buddhism: A History of Coexistence

The Essence of Shinto

Shinto, Japan’s indigenous religion, is fundamentally rooted in nature worship. It posits that divinities (kami) reside in forests, trees, plants, rivers, and throughout the natural world—a concept known as “eight million gods” (yaoyorozu no kami). Humans, sustained by the bounty of nature, are expected to express gratitude toward these natural elements. Shinto lacks rigid doctrines or commandments, instead emphasizing customs centered on harmony with nature and reverence for ancestors.

The Essence and Adoption of Buddhism

Buddhism, founded on the teachings of the Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama), arrived in Japan via China in the 6th century. It encompasses both philosophical aspects—focused on liberation from suffering—and religious dimensions involving faith in various Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Japanese Buddhism belongs to the Mahayana tradition and has diversified into numerous sects including Tendai, Shingon, Jodo (Pure Land), and Zen.

When Buddhism was initially introduced to Japan, it encountered opposition from Shinto practitioners (notably the conflict between the Soga and Mononobe clans). However, over time, the two traditions gradually synthesized. The polytheistic nature of Shinto facilitated the relatively smooth adoption of Buddhism, as the absence of an absolute monotheistic deity allowed for the flexibility to accept Buddhist deities alongside indigenous kami.

Shinbutsu-Shūgō: The Syncretic Fusion

This syncretic relationship between Shinto and Buddhism, known as shinbutsu-shūgō (神仏習合), became a defining characteristic of Japanese religious practice from the Nara period (710-794) through the medieval era. The fusion was based on the belief that Japanese kami and Buddhist deities were fundamentally the same beings in different manifestations—a concept called honji suijaku (本地垂迹), which held that Buddhas and bodhisattvas manifested themselves as Shinto deities to guide the Japanese people.

This religious syncretism manifested physically in Japan’s sacred spaces. Many Shinto shrines maintained Buddhist temples on their grounds (called jingūji), while Buddhist temples often incorporated Shinto elements. Priests developed complex theological frameworks to integrate both traditions, and religious rituals frequently combined elements from both. This harmonious coexistence allowed Japanese people to participate in both religious traditions simultaneously—a practice that continues in modern life, with many Japanese visiting Shinto shrines for New Year’s blessings and life celebrations, while turning to Buddhist temples for funeral rites and ancestor veneration.

Japanese Buddhist temples transcend their religious function, serving as repositories of historical and cultural heritage. Many temples house architecturally significant structures and Buddhist statues designated as Important Cultural Properties or National Treasures, enhancing their historical and artistic significance.

Changes Since the Meiji Era

The syncretic relationship between Shinto and Buddhism was officially severed during the Meiji Restoration with the government’s shinbutsu bunri (神仏分離) policy in 1868, which forcibly separated the two religions. This led to widespread destruction of Buddhist elements in Shinto shrines and the removal of Shinto elements from Buddhist temples.

From the Meiji Restoration until the end of World War II, Shinto was established as the state religion (State Shinto), incorporating elements that diverged from traditional Shinto practices, including the deification of the emperor. Following Japan’s defeat in WWII, the emperor’s “Declaration of Humanity” dismantled State Shinto. Nevertheless, shrines continue to form an essential component of Japanese culture to this day.

Despite this official separation, the centuries of integration left an indelible mark on Japanese spiritual consciousness. Many Japanese today still practice elements of both religions without perceiving any contradiction—a living legacy of the long history of syncretic worship in Japan

Distinguishing Shrines from Temples: Fundamental Knowledge

Characteristics of Shinto Shrines

- Torii: Gates marking the entrance to sacred shrine grounds

- Sandō: The approach leading from the torii to the worship hall

- Chōzuya/Temizuya: Water pavilions for ritual purification before worship

- Haiden: The hall where worshippers offer prayers

- Honden: The main sanctuary housing the deity (typically not open to the public)

- Shinmon: Emblematic symbols similar to family crests that identify each shrine

Characteristics of Buddhist Temples

- Sanmon: The main gate marking the entrance to temple grounds

- Hondō/Daidō: The main hall enshrining the principal Buddha statue

- Shōrō: Bell tower housing the temple bell

- Gojūnotō: Five-storied pagoda built to house Buddha’s relics

- Buddha Statues: Principal and attendant Buddha figures enshrined within the temple

- Cemeteries: Many temples have adjoining burial ground

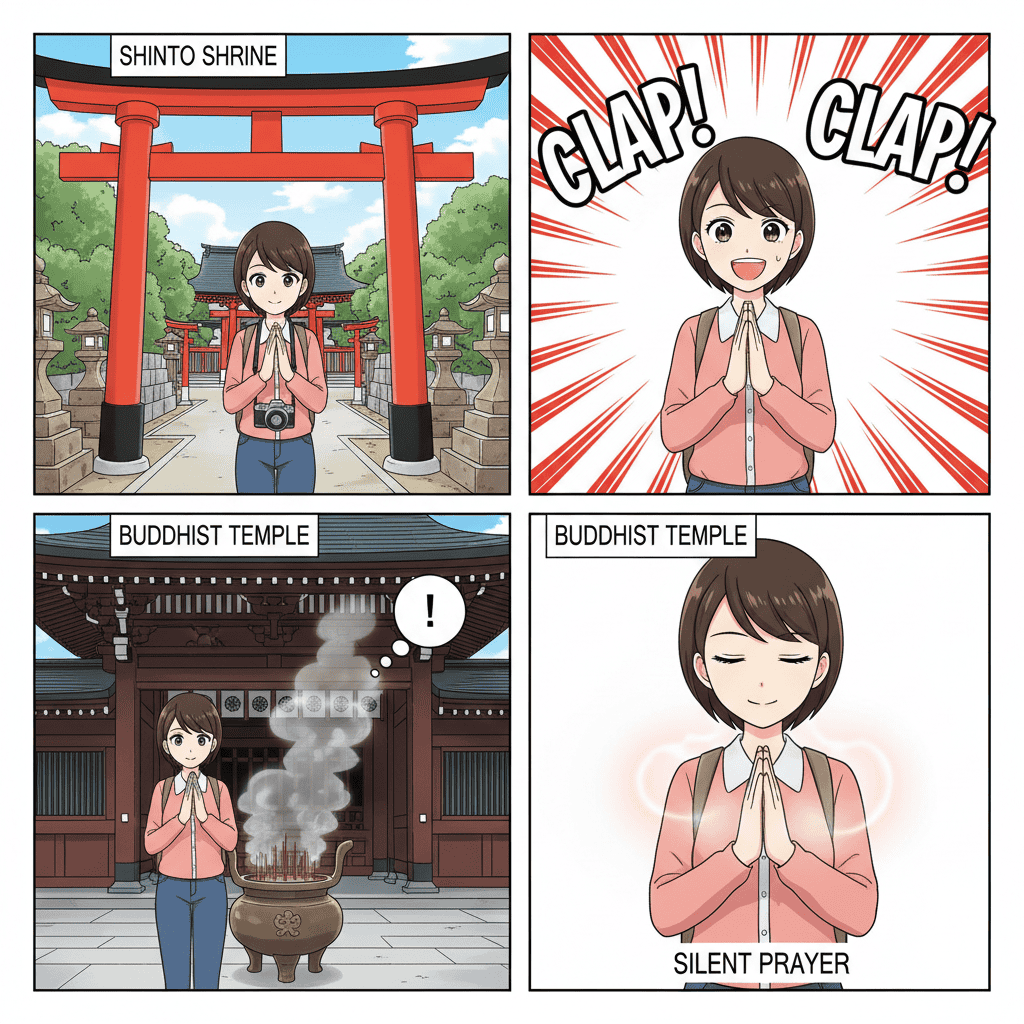

Differences in Worship Practices

How to Worship at Japanese Shrines and Temples

Shinto Shrine Protocol

Buddhist Temple Protocol

These protocols are guidelines, not strict rules. Most Japanese people appreciate foreigners making an effort to follow traditional customs, even if not performed perfectly.

Tokyo’s Representative Shrines and Temples

In Tokyo, numerous magnificent shrines and temples await visitors. Below are two particularly prominent sacred sites that are especially popular among international tourists. More detailed information about these locations is available in separate articles.

Meiji Jingu (Shibuya Ward)

– A shrine dedicated to Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken, established in 1920 – A tranquil sanctuary encompassing approximately 700,000 square meters of forest in the heart of Tokyo – One of Japan’s most visited shrines, welcoming about 3 million visitors during the New Year period – Features “Kiyomasa’s Well,” a popular power spot frequently visited by celebrities – Shinto weddings can often be observed, particularly on Sundays – Access: 5-minute walk from JR Harajuku Station.

Sensō-ji(Taito Ward)

-Tokyo’s oldest temple, reportedly founded in 628, belonging to the Jodo sect of Buddhism – Globally renowned for its Kaminarimon (Thunder Gate) and approximately 200-meter Nakamise shopping street – Enshrines Kannon Bodhisattva (Avalokiteśvara), also known as “Asakusa Kannon” – Houses Important Cultural Properties including a five-storied pagoda and Hōzōmon gate – Hosts vibrant annual events including New Year celebrations, Setsubun, and the Sanja Festival – Access: 5-minute walk from Asakusa Station on the Tokyo Metro Ginza Line.

Experiential Religious Culture in Tokyo’s Shrines and Temples

Tokyo offers opportunities not only for sightseeing but also for engaging directly with Japan’s traditional religious practices. These experiences can be particularly memorable for international visitors.

Shakyo (Sutra Copying) Experience

Shakyo is a Buddhist practice of hand-copying sutras, believed to enhance concentration and induce mental tranquility. Several venues in Tokyo offer this experience to foreign visitors.

Preview

Zōjō-ji(Minato Ward) –

A prominent Pure Land Buddhist temple, historically serving as the Tokugawa family mausoleum – Offers shakyo sessions with English guidance several times monthly – Sessions typically last about 60 minutes and cost approximately 2,000 yen – Advance reservations required through the official website – Provides an excellent photo opportunity with Tokyo Tower in the background – Access: 3-minute walk from Onarimon Station on the Toei Mita Line

Sengaku-ji (Minato Ward) –

A temple famous for its connection to the 47 Ronin (Loyal Retainers), offering a serene environment for sutra copying – Regularly scheduled sessions, primarily on weekends, with English materials available – Participation fee of approximately 1,500 yen, including tea and sweets – Opportunity to learn about the temple’s historical significance simultaneously – Access: 5-minute walk from Sengakuji Station on the Toei Asakusa Line

Zazen (Seated Meditation) Experience

Zazen is a meditative practice central to Zen Buddhism, involving sitting in proper posture to cultivate mental clarity. The practice often includes the unexpected “encouragement tap” with a wooden stick (kyōsaku) to help maintain focus and proper posture, as demonstrated in the video below.

Preview

For those interested in experiencing zazen firsthand, Tokyo offers several beginner-friendly venues:

Kenchō-ji Tokyo Branch Temple, Tōzen-ji (Minato Ward) –

Tokyo branch of Kenchō-ji, the foremost of Kamakura’s Five Great Zen Temples – Regular zazen sessions for foreigners with instruction available in English – Detailed guidance for beginners, including posture correction – Approximately 90-minute sessions for around 500 yen – Sometimes includes matcha tea and Japanese sweets afterward – Access: 10-minute walk from Akabanebashi Station on the Toei Oedo Line

Ryōgoku Ekō-in (Sumida Ward)

A temple located near sumo stables, offering insights into the relationship between sumo and Zen – Monthly zazen sessions accessible to foreign participants – No reservation required, with participation fees around 1,000 yen – English explanations available, making it accessible for beginners – Access: 5-minute walk from Ryōgoku Station on the JR Sobu Line

Observing Shinto Weddings **Meiji Jingu** (Shibuya Ward)

-Traditional Shinto weddings frequently held on weekends – Visitors may chance upon a wedding procession – Opportunity to see traditional Japanese wedding attire including “shiromuku” (white kimono) and “iro-uchikake” (colored kimono) – Photography is permitted from a distance, but discretion and respect for the ceremony are essential – Access: 5-minute walk from JR Harajuku Station

Collecting Goshuin (Temple/Shrine Seals)

Goshuin are calligraphic seals and inscriptions that serve as evidence of one’s visit to a shrine or temple. This activity has recently gained popularity among foreign visitors.

Preview

Goshuin Basics

Purchase a dedicated goshuin-chō (seal book) for 1,000-2,000 yen – Visit the administrative office or amulet hall of shrines and temples to receive the seal – Each location offers unique designs, with some featuring seasonal variations – A customary offering of 300-500 yen is typically expected

Recommended Goshuin Locations for Foreign Visitors

**Meiji Jingu**Staffed with personnel who can explain the meaning of goshuin in foreign languages –

**Sensō-ji**: Easily accessible during sightseeing, with English guidance available –

**Kanda Myōjin**: Popular among younger visitors for its anime and game collaboration goshuin –

**Zōjō-ji**: Collectible while enjoying the view of Tokyo Tower

Seasonal Events at Tokyo’s Shrines and Temples

Throughout the year, Japan’s shrines and temples host various seasonal ceremonies that offer excellent opportunities to experience Japanese religious culture.

Hatsumōde (First Shrine/Temple Visit of the New Year

A traditional custom celebrating the New Year, when many Japanese visit shrines or temples to pray for happiness in the coming year.

**Meiji Jingu** – The most visited hatsumōde destination in Japan (over 3 million visitors annually) – Gates remain open overnight from December 31st to January 1st – Sweet sake or sacred sake sometimes offered after prayers – To avoid crowds, visiting after January 2nd is recommended

**Sensō-ji** – A popular New Year destination among international tourists – Beautiful illumination of the five-storied pagoda – Food stalls along Nakamise Street create a festive New Year atmosphere

Setsubun (Around February 3rd)

A seasonal observance marking the transition between seasons, featuring bean-throwing ceremonies at religious sites to expel evil spirits. **Zōjō-ji** – Popular event featuring bean-throwing by celebrities – Lucky bean lottery draws may be held – May require advance registration **Sensō-ji** – Bean-throwing ceremonies performed by famous personalities and sumo wrestlers – The lively, crowded atmosphere makes for photogenic opportunities/

Preview

Hanami (Cherry Blossom Viewing, Late March to Early April)

Visiting shrines and temples during cherry blossom season offers the aesthetic pleasure of seeing historical structures juxtaposed with beautiful blossoms. **Yasukuni Shrine** – Contains approximately 1,000 cherry trees, known as “Yasukuni’s Cherry Blossoms” – Evening illumination with traditional paper lanterns – Food stalls add to the festive atmosphere during blossom season **Ueno Tōshō-gū** – A shrine within Ueno Park, one of Japan’s most famous cherry blossom destinations – The contrast between the golden shrine building and the cherry blossoms is particularly striking – The “Peony Festival” is also held in early April

Preview

Sanja Matsuri (Late May)

A vibrant traditional festival celebrating the three founders of Asakusa, featuring over 100 portable shrines (mikoshi) carried through the streets.

Sensō-ji and Asakusa Shrine

- One of Tokyo’s three major festivals, held on the third weekend of May

- Originated from the discovery of a Kannon statue in the Sumida River in 628 CE

- A perfect example of the historical fusion between Buddhism and Shinto

- The vibrant atmosphere and traditional costumes make it highly photogenic

- Access: 5-minute walk from Asakusa Station on Tokyo Metro Ginza Line

Shichi-go-san (Around November 15th)

A celebration of children’s growth at ages three, five, and seven, offering opportunities to see children in colorful traditional attire. **Meiji Jingu** – A standard destination for Shichi-go-san visits, especially crowded on November weekends – An excellent opportunity for foreign visitors to glimpse Japanese family culture – Families taking commemorative photographs can be seen throughout the grounds **Hie Shrine** (Chiyoda Ward) – A shrine associated with Tokugawa Ieyasu, popular for Shichi-go-san visits – Affectionately known as “Sanno-sama” with convenient access – Access: 3-minute walk from Akasaka Station on the Tokyo Metro Chiyoda Line

Preview

## Etiquette Guide for Foreign Visitors

Iconic Shrines and Temples of Japan

Beyond Tokyo, Japan boasts numerous extraordinary shrines and temples worthy of a visit. If time permits, consider exploring these revered sites.

Preeminent Shinto Shrines

Ise Jingū (Mie Prefecture)

- Japan’s most sacred shrine, dedicated to Amaterasu Ōmikami (the Sun Goddess)

- Comprises two main sanctuaries—the Inner Shrine (Naikū) and Outer Shrine (Gekū)—along with approximately 125 subsidiary shrines

- Maintains the tradition of rebuilding the main sanctuary every 20 years (Shikinen Sengū), most recently in 2013

- “Okage Yokochō,” the adjacent traditional shopping district, offers regional cuisine and souvenirs

- Approximately 3 hours from Tokyo via Shinkansen and bus

Izumo Taisha (Shimane Prefecture)

- Dedicated to Ōkuninushi-no-Ōkami, a deity associated with relationship formation and matchmaking

- Attracts worshippers nationwide seeking blessings for relationships

- Famous for its enormous sacred rope (shimenawa), measuring 24 meters in height

- October is known as the “Month of the Gods” (Kannazuki), when deities from across Japan are believed to gather here

- Approximately 3.5 hours from Tokyo via plane and train

Itsukushima Shrine (Hiroshima Prefecture)

- A UNESCO World Heritage Site distinguished by its vermilion torii gate and shrine buildings constructed over water

- Offers varying vistas depending on the tides, creating a mystical atmosphere

- The island’s wild deer add to its appeal for tourists

- Evening illumination creates a romantic atmosphere

- Approximately 4.5 hours from Tokyo via Shinkansen and ferry

Preeminent Buddhist Temples

Kiyomizu-dera (Kyoto Prefecture)

- A UNESCO World Heritage Site founded in 778, emblematic of Kyoto

- Famous for its “Kiyomizu Stage,” a veranda extending 13 meters above a hillside offering spectacular views

- The grounds include attractions such as Otowa Waterfall and Jishu Shrine

- Particularly beautiful during cherry blossom season and autumn foliage

- Approximately 2.5 hours from Tokyo via Shinkansen and city bus

Kinkaku-ji (Kyoto Prefecture)

- Officially named “Rokuon-ji,” renowned for its golden pavilion with upper two floors covered in gold leaf

- Originally a villa of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu converted into a temple, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site

- The Gold Pavilion (Shariden) creates a stunning reflection in the Mirror Pond (Kyōko-chi)

- The garden exemplifies the Muromachi period’s landscape design

- Approximately 2.5 hours from Tokyo via Shinkansen and city bus

Hōryū-ji (Nara Prefecture)

- Known as the world’s oldest wooden structures, founded by Prince Shōtoku in 607

- Preserves 7th-century architecture including its five-storied pagoda and main hall, designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site

- Houses approximately 2,300 Important Cultural Properties and National Treasures

- Displays numerous artifacts associated with Prince Shōtoku

- Approximately 3 hours from Tokyo via Shinkansen and train

– Traditional etiquette involves a slight bow before passing through the torii gate – Water Purification Ritual: Right hand → left hand → mouth → left hand again (do not directly take water into your mouth) – Place monetary offerings quietly (rather than tossing them) – The traditional sequence is two deep bows → two hand claps → one final bow

**Temple Worship**: – Offer a slight bow at gates or before Buddha statues – Join hands in prayer before the main hall (without clapping, unlike at shrines) – Incense Ritual: Hold incense between thumb and index finger, raise it to forehead height, then place it in the incense burner While strict adherence to these practices is not mandatory, familiarity with them demonstrates respect for Japanese cultural traditions.

## Iconic Shrines and Temples of Japan Beyond Tokyo, Japan boasts numerous extraordinary shrines and temples worthy of a visit. If time permits, consider exploring these revered sites.

Conclusion

Japan’s shrines and temples serve dual roles as religious institutions and repositories of historical and cultural heritage. For foreign visitors to Tokyo, exploring these sites offers an invaluable opportunity to develop a deeper understanding of Japanese culture. By observing fundamental etiquette and respecting the atmosphere of each location, visitors can enjoy a more enriching experience. Learning to distinguish between shrines and temples and practicing their respective worship protocols elevates the visit beyond mere tourism to a genuine cultural immersion. Just as many Japanese visit shrines and temples as a natural part of their lives, foreign visitors should feel welcome to approach these sacred spaces with a relaxed attitude. While these are indeed sacred sites, excessive anxiety is unnecessary. Visitors are encouraged to appreciate the serene atmosphere and historical significance of Tokyo’s shrines and temples at their own pace.

コメント

コメント一覧 (1件)

[…] Shrines and Temples 101: The Definitive Guide for Foreign Visitors to Tokyo Japan's religious landscape differs markedly from that of many other nations around the world. […]